Pachaiyappa Mudaliar - THE GREAT PHILANTHROPIST [1754 -1794]

Our College is a unit of Pachaiyappa's Charities. It will be of immense interest to know about Pachaiyappa, the father of the Charities.

Pachaiyappa Mudaliar was born in 1754 in Periapalayam, some forty miles to the northeast of Kanchipuram. His father Viswanatha Mudaliar, a native of Kanchipuram, had died few months earlier to his birth and leaving his family in distress. When Pachaiyappa was five years of age, his mother took him to Madras along with his two sisters and lived in a small house in Swamy Maistry Street. There she sought the protection of one Mr. Narayana Pillai, a wealthy Dubash in the service of the Powneys, an influential English family merchant. Narayana Pillai with his characteristic generosity, treated her as his own sister and educated young Pachaiyappa in account keeping, correspondence and the rudiments of the English language.

Pachaiyappa quickly learnt English and was all set ready for business. He first became a small scale agent of goods imported by the English merchants of Madras and also purchased supplies for export too. Mr. Narayana Pillai got him appointed as a Dubash under one Mr. Nicholas, a travelling merchant in Tamil Nadu Districts. In this capacity, he travelled widely in the south and made some money. Even in those early years he was deeply religious minded. In 1774, when he was only twenty he built the Kalyana mandapam of the Ekambareswarar temple at Kanchipuram and was responsible for two sacred images to be installed in that temple. He had the Kumbabishekam celebration performed on a grand scale.

In 1776, Pachaiyappa extended his business transactions in Chengleput District and became the most successful negotiator of loans. He undertook to pay the East India Company, in cash the land tax due to them from several groups of villages. He also transacted agency business between the English merchants and the officials of the court of the Nawab of Carnatic and earned the gratitude of both the parties. Soon after, he became the Senior Dubash of Mr.J. Sullivan, a member of the Civil Service of the East India Company who was appointed as British Political Agent at the Durbar of the Carnatic Nawab. In 1783 when Mr. Sullivan became the Chief Civil Administrator in Trichy, Pachaiyappa Mudaliar was appointed as his assistant to provide the necessary supplies to the army. Pachaiyappa's earnestness of purpose, persuasive power, capacity for organisation and the success that followed his work won him appreciation of the authorities.

Shortly after this, Pachaiyappa entered the service of the Rajah of Tanjore. The Rajah had found it hard to pay his annual tribute regularly in one uniform coinage. Pachaiyappa acted as an agent for making remittances of the Rajah's annual tribute to Madras in regular instalments and received a commission of 10 to 20% on the sums remitted. He also successfully negotiated the terms of the peshkash of several polygars of the southern country subject to the Nawab of Carnatic. In these ways he amassed a handsome fortune of about twenty lakhs of Rupees and built a spacious house for himself at Komaleswaranpet named after him. In 1787, after Amar Singh ascended the throne of Tanjore. Sir Archibald Campbell, the Governor of Madras appointed Pachaiyappa Mudaliar to assist Mr. William Petric, Commissioner for the realization of the revenues of Tanjore. Pachaiyappa had to lend a large sum of money to the Rajah to enable him to pay his arrears of tribute to the East India company. After the necessary arrangements were made for regular remittance of the annual tribute from Tanjore, Mr. Petric returned to Madras, while Pachaiyappa continued to stay on at the Rajah's court maintaining a high style of living with all the dignity attached to his position of importance.

His position and prestige at the court of Tanjore evoked the envy of the European residents of Tanjore, who complained to the Madras Government that some money- lenders and Pachaiyappa, were lending money to the Rajah, at exorbitant rates of interest and were thus encouraging him to indulge in extravagant expenditure and that their removal from Tanjore would benefit both the people and their Prince. In this connection Pachaiyappa had to go over to Madras to insist on the continual of his own position at the court of Tanjore and how his removal would be in contravention of Sir Archibald Campbell's special order of appointment. An investigation followed and Pachaiyappa was completely exonerated in 1791.

It was during his stay at Madras in 1791 that Pachaiyappa made his endowments to the Sri Sabhanayaka shrine at Chidamabaram. He arranged for embellishment of the inner sanctum and for the renovation of the superstructure of the east gopuram. In the gateway of the tower are still to be seen the images of Pachaiyappa and his sister Subbammal. He also made a gift of a large number of silver vessels used in the daily worship of the Deity and several ornaments of inestimable value. He provided a new Car for Deity and constructed a mandapam for it and instituted a new annual Brahmotsavam festival known as Ani Tirumanjanam, for the observance of which he later made provision in his Will.

Pachaiyappa returned to Tanjore in 1792 and resumed his duties and also carried on his banking business. Pachaiyappa had no sons. He had first married his sister's daughter. As he had no child by her, he married for the second time when he was residing at Tanjore by whom he had a daughter. But his health had failed and he was then an ailing man. When his illness, became rather serious, he proceeded to Kumbakonam for treatment and during his short stay there, he completed the construction of a choultry which he had begun sometime before. It was at Kumbakonam on 22nd March, 1794, that he drew up his famous Will "dedicating with full knowledge and hearty resignation of all his wealth, in the absence of any male issue, to the sacred service of Siva, Vishnu and to certain charities at various temples and places of pilgrimage, to the erection of religious edifices, to bounties to the poor, to seminaries of Sanskrit learning and to other objects of general benevolence. " On the 24th March he sent an autograph letter to his old Patron Narayana pillai saying that his end was near and requesting him to settle all his affairs including prompt payment of every pie due from him to others. He then proceeded to Tiruvaiyar, a sacred place to the northwest of Tanjore and there breathed his last on the 31st March, 1794. He was only forty when he died. The sacred places which immediately benefited by his bequests are Chidambaram, Sirkazhi, Thiruvidaimarudur, Kumbakonam, Thiruvaiyar, Jambukeswaram, Srirangam, Tanjore, Thiruvottiyur, Madurai, Rameswaram, Kanchipuram, Thiruvarur, Thiruvannamalai, Triplicane and even the distant Benares.

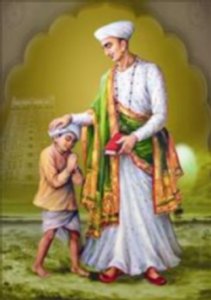

Pachaiyappa Mudaliar was among the foremost Dubashis of his time. He was simple, kind-hearted and God- fearing man, ever inclined to pity the poor and used his money and influence for their relief. He kept a large establishment for dispensing hospitality. He was of a fair complexion with broad forehead and bright intelligent eyes. In appearance and dress he was simple, attractive and dignified. His popularity, wherever he went, was amazing. His name was on everybody's lips on account of his wide sympathy and benevolent charities. His was the remarkable career of a self- made man, who though born and brought up in poverty, rose by his own force of character and genius to be the richest man of his time but who finally gave away all his riches for the service of God and humanity.

In those days 'Wills' were almost unknown and their validity was scarcely recognised. The consequence was that for many years successive executors neglected the provisions of Pachaiyappa's Will and misappropriated the funds therein settled. Fortunately, the matter came to the notice of Sir Herbert Crompton, the then Advocate-General who there upon filed information in the Supreme Court and obtained a decree against the person finally liable for the performance of the charities and also for an account of the funds with accumulated interest, amounting to many lakhs of Rupees. However, the person against whom the decree was passed could only pay small portion of his liabilities. Thiru George Norton, the next Advocate-General succeeded in recovering a large quantity of jewels and thereby realising in respect of the claim a total sum of about eight lakhs of Rupees. In a further decree passed in 1841 prepared a scheme whereby, in duo harmony with the provisions of the Will and without touching upon any specific religious or benevolent bequests therein mentioned, it was directed that all accumulation, beyond one lakh of pagodas (Rs. 4,50,000/-) should be devoted to educational establishments in various parts of the Presidency, and particularly in the city of Madras. The control of these endowments became vested by law in the Board of Revenue which, under instructions from Lord Elphinstone's Government embodied the Scheme of the Supreme Court in a kind of Letter Patent and created a body of Hindu Trustees to administer the whole and carry out the benevolent intentions of the testator.

A school was established in the town of Madras in January, 1842 under the name of Pachaiyappa's Central Institution for the purpose of imparting gratuitous education to the poorer classes of the Hindu Community. This school became very popular and it had developed into the present Pachaiyappa's College, Madras.

The usefulness of Pachaiyappa's benefaction has been augmented by the generosity of enlightened members of the Hindu Community who put the Trustees in-Charge of large funds to be utilised for educational purposes. Some of those benefactors were Ami Govindu Naicker, P. T. Lee Chengal- Naicker, Oleti Ranganayaki Ammal, Chellammal and Kandaswami Naidu.

The late Thiru C. Kandaswami Naidu of Aminjikarai, Madras had made the Trustees residuary beneficiaries of his vast estate. In the year 1967, two Colleges were started in his name, one at Cuddalore for Women and another one at Madras for Men.

At present the charities manage six colleges of which three are for women, and a number of schools catering education to thousands of students in the cities of Madras, Kanchipuram, Cuddalore and Chidambaram. All these developments have augmented the usefulness of these institutions which have filled a very large and laudable place in the cultural life of South India for over a century.

Pachaiyappa Mudaliar [1754 -1794]